Street Life: The Story Behind The Book | November 3, 2023

The year was 2010. My first academic book, Punished: Policing the Lives of Black and Latino Boys, had just been released by a top university press. It was the story of the many ways in which marginalized young people are abandoned and punished by schools, law enforcement, and their communities, and how this leads to delinquency and a lack of educational attainment. I had researched a new generation of young people from my own world, having once been in the gang life on the streets of Oakland before making it through college and beyond. Proud of how Punished could help make a difference for teens who were growing up in oppressive conditions like I had, I went back to Oakland to find the young men whom I had followed for three years to tell their stories.

As I approached the corner of 85th and International in Oakland I spotted one of the young men I had studied, a nineteen-year-old Latino. I asked him to give me feedback, to tell me what he thought about Punished. I returned a few weeks later that summer and asked his opinion. “It’s all right,” he told me. After an awkward, silent pause, he lowered his voice and said, “But it don’t speak to me,” while checking a text message on his phone.

In that moment, my heart sunk deep into the bottom of my stomach, giving me an instant bellyache. The pain in my stomach sent shock waves through my spine, concluding at my thinking brain. I reasoned to myself, “I have failed these young people. How could I write a book about them that they could not relate to?” The book was too academic, too abstract, too detached from the very community I wanted to reach the most.

I arrived home that night with a guilty conscience, a hurting heart, and an angry soul. Long nights of lost sleep haunted me. For days I couldn’t talk about what happened, until I awoke in the middle of one night, and my wife, Rebeca, was made aware of it all.

That Tuesday night, I’d given up any last hope of getting back to sleep, and my right foot began nervously swinging from side-to-side, making the bed rock ever so slightly, like a boat cradled on a serene ocean. The subtle motion was enough to stir Rebeca. With the coarse, raspy voice of someone just waking up, she asked, “Why aren’t you asleep?” She turned her warm, beautiful body toward me—I could see the white of her eyes flicker open in the semi-darkness.

“I can’t stop thinking about those boys,” I told her.

“The Oakland boys?”

“Yes, the boys in my book” I responded, feeling desolate and drowning in a deep despair.

“If you can’t sleep and you’re feeling bad about the book,” Rebeca told me, “then get out of bed and write another book!”

“Good idea,” I whispered. I pulled the covers off, eased my way out of bed, and told her good night as I walked to the dingy-grey, broken-wooden-foot Ikea sofa in the living room of our crowded apartment in Isla Vista, California.

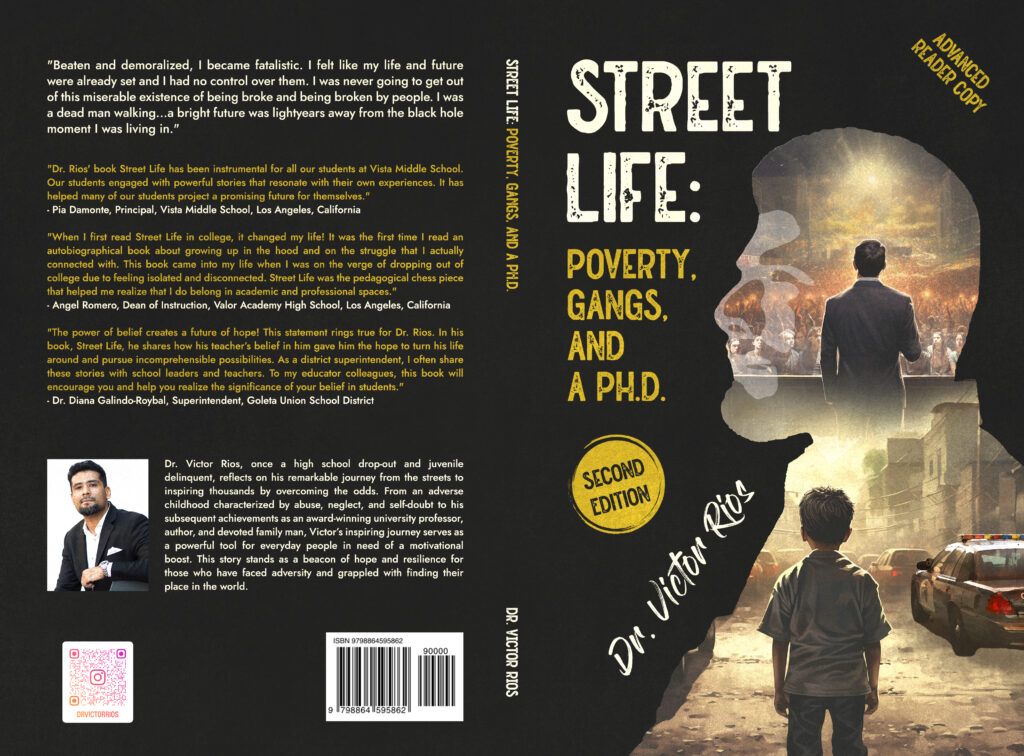

And so I sat, with my laptop in hand, to write this book meant to speak to young people like those I had studied—young people who live on the margins, who are often assigned texts that do not represent their communities, cultures, lived realities, struggles, or experiences. My hopes more than a decade ago were simple: to give Street Life away to a few at-promise students and maybe motivate them to overcome their struggle. I thought it could be a resource that I’d pass out to young people I met in my journeys, to give them some hope and inspiration. I imagined a few teachers using the book as well, in classes with their struggling students. Maybe I could give away one hundred copies and that would lead to selling one hundred more, I thought.

But the sails of this book picked up wind along the way and it became widely read. Over 50,000 copies have sold. Teachers use it with their middle school and high school students, and school districts order it for their teachers to read as a guide on how they can inspire their students to prosper. In addition, university and community college professors have assigned it in their English, Biography, Journalism and Writing courses, while dozens of juvenile justice facilities and high schools order copies for their students. Students contact me to tell me that this book has changed their lives. I am humbled.

One school, Moreno Valley College in Moreno Valley, California, even adopted Street Life as its One Book, One College reading. The entire college community read the book and had events and conversations about it throughout the academic year. My favorite accolade for the book was learning by email from a continuation school teacher that her students had turned this book into a film. Each chapter had become a segment of the film that was on YouTube briefly (due to copyright issues with Kendrick Lamar songs they used in the background). The segments captured parts of my life, like being in fights, meeting my wife, being a father, and graduating from school. The students acted out each part of my life, and I was filled with pride and emotion as I watched them in their stellar performance. The teacher told me that the students were so inspired and empowered by the book, they decided to create the film beyond their assigned work. They stayed after school, on their own, to complete the project!

Rebeca’s advice ignited an ambition: to tell my story with the aim of making a connection with youth that were experiencing similar struggles and did not know where to turn. My hope was that anyone that picked up this book needed guidance and inspiration could find it in its pages.

There was a time, in 2022, when I felt vulnerable about the book. For some reason I felt that I had disclosed too much, that I had put my personal life out there for the world to critique. I decided to put the book out of print—it would no longer sell, no longer exist. I needed some privacy. Around this time I gave a keynote address at an event taking place at the Santa Clara Convention Center. Afterwards, as I met the guests, one young man, in his late 20’s approached me. He was a gang intervention worker for the city of San Jose, California. As I shook his hand he told me, “Dr. Rios, your book changed my life.” I thanked him and he proceeded to explain. He told me that when he was in high school his teacher told him to read my book. He told his teacher he wasn’t interested and left without even picking up the book. A few months later his brother was murdered. It was a rough time for him. He went back to his teacher to ask him for guidance. His teacher pointed to Street Life, which still sat on his desk, and said, “read the book.” He read the book and it helped him in the journey to build a legacy in his brother’s name.

After meeting this young man I decided I needed to keep the book in circulation. If my story could help him, I now knew that it could continue to help others. His story inspired me to produce this second edition.

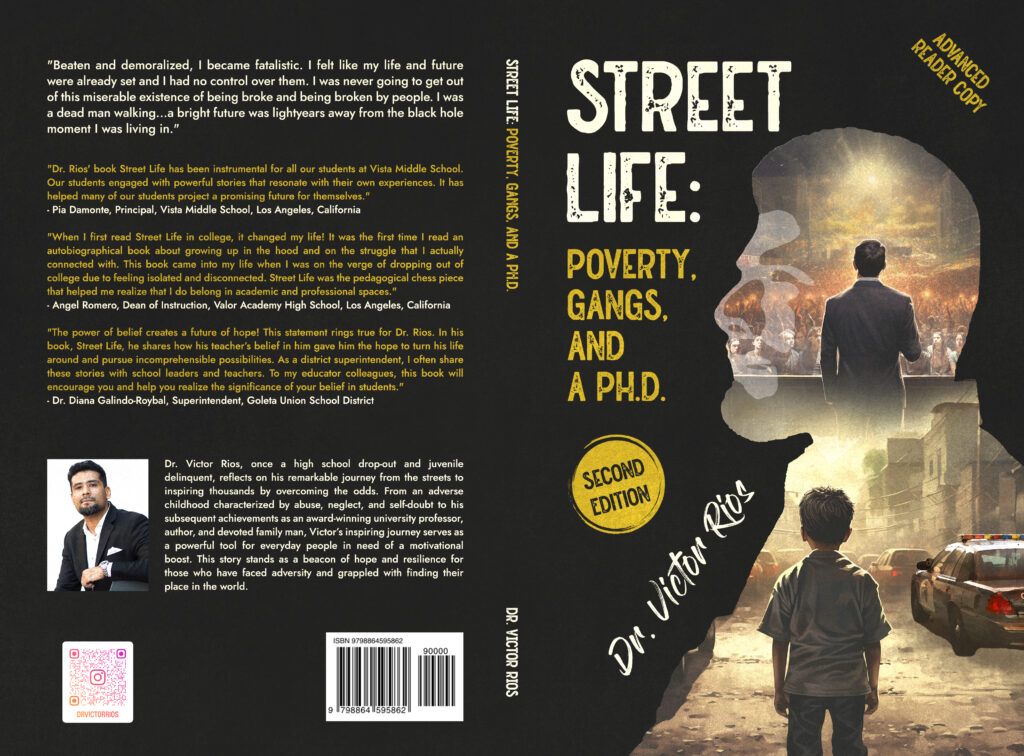

- Dr. Victor Rios